When divorced father of two Pino Rodriguez decided to return to Royden Street, he chose an apartment two doors down from his aging mother, to be accessible when she needed him. That was more than 15 years ago. Pino was a renter, his mother a homeowner. The Lanning Square neighborhood in West Camden had always had its share of problems—poverty, crime, drugs—and, in Pino’s opinion, a sort of communal depression, in which no one felt safe. “I wasn’t able to have my children spend any nights. You know—sleepovers—because their mother said it was unsafe. And she was absolutely right.” He recalls lying down on the floor several times daily, hoping to avoid the stray bullets that screamed through the air.

“I wasn’t able to have my children spend any nights. You know—sleepovers—

because their mother said it was unsafe. And she was absolutely right."

Seniors, such as his mother, Pino explains, respond to the problems in the street by shutting themselves in. “They tend to just say, Ok, I won’t go out there anymore. So you find the seniors, what they do is they shelter in the house and use their backyard. So when you ask them about, ‘Did you hear this, did you . . . ‘ they don’t realize none of that because they kind of put it out of their mind, their sight.”

Pino resolved that living with this level of fear and uncertainty was unacceptable—for his mother, for the other seniors in the neighborhood, and for his children. With the $50 he had left each month after paying his rent and child support—which he is very proud to say he never missed—he instituted some changes in his neighborhood. “I started putting flower boxes in the senior citizens’ windows, so people were like, Oh, what’s that? What you doing? And, you know, They’re going to steal that. And I’m like, ‘Let them take it.’ You know, as long as it didn’t cost that much.”

As the flowers took root in Pino’s community, so did his positivity. Neighbors became involved in the effort and began to take more pride in their community. They started spending more time outside, working together—whether it was to collect garbage, decorate for the holidays, even paint the curblines when the city said they didn’t have the resources to do that. They also attended meetings to urge the city to do their part, but their elected officials weren’t as supportive.

Residents had been lobbying for some time to get the city to repair the roads and sidewalks, tear down abandoned properties, and clean up empty lots. But, Pino explains, the city had always shifted responsibility back on them, saying “You need to step up. You need to take back your neighborhood.” Eventually, he says, frustrations grew. “We did that. We got involved. We helped our residents clean up the front of their homes. ... We accepted responsibility. We started a program called the Block Supporter Initiative … and got rid of the drugs, as much as we can.” And yet, still there was no response from the city to their requests for help. “So, lo and behold, before you know it, you start—you get things in the mail and you start hearing rumors about that they’re going to take your home.”

A new initiative of the 2003 state takeover of Camden was to try to designate the entire city, one neighborhood at a time, as blighted or, in the language of the redevelopment laws, as “areas in need of redevelopment,” according to Legal Services attorney Olga Pomar. “It basically meant that all property owners in Camden would be under this threat that at any time, for the next 25 years, the city could take their home.

“The city administration would have the powers of eminent domain over every single property in the city of Camden—meaning that at any time, they could force the owner of the property to sell it against their will, for what the city determined was a fair reasonable price, usually considerably less than what the person would need to relocate to a more desirable place to live.” The justification behind that, she says, was that “drastic government intervention was what was needed to turn around this city that everybody saw as the poster child of blighted urban America.”

Situated near Cooper Hospital and Medical School and the UMDNJ campus, Lanning Square is in a prime location for expansion to accommodate the growing needs of the university and student housing. Even without a solid plan for redevelopment, the city proposed to take 220 homes in Lanning Square alone by eminent domain and bulldoze large sections of the neighborhood in anticipation of future development. With a redevelopment designation and plan in place, there would be no RFP (request for proposal) process or opportunity for public scrutiny over redevelopment agreements, explains Olga. The city could basically designate redevelopers to develop a plan for areas of the city with little incentive to solicit community input. The city proceeded to approve unanimously the plan to designate Lanning Square as a redevelopment area and authorize use of eminent domain, despite strong opposition from the residents.

“We would get, you know, things like, for instance, next question, and they would go and talk to somebody else in the room and things like that. So it was very frustrating … when you do step up, it’s very frustrating to see or feel like they turned their backs on you. … To do all those things like that and to receive something saying that you’re going to be put out is a total slap in the face.

”With the help of South Jersey Legal Services, Olga represented Pino’s mother, along with 48 other concerned residents and a community group, to sue the city of Camden, arguing that their homes were not blighted, and therefore shouldn’t be subject to being taken by eminent domain. Other eminent domain cases involving other Camden neighborhoods that were playing out at the same time worked to the advantage of the Lanning Square West Residents Association, as residents and businesses opposing the City’s plans won some victories in court. Eventually, when new mayor Dana Redd inherited mounting legal bills and increasingly negative press attention, she concluded quickly that settling with the residents was more appealing than continuing this protracted legal battle. In 2008, a settlement was finally reached whereby only abandoned and vacant properties were declared blighted and could be taken by eminent domain—not any occupied residences. This success was an enormous relief to those who were at risk of losing their homes. And yet, given the location of the homes, with the 25-year redevelopment designation still in place, the threat of eventual displacement remains and many people fear that their homes are still at risk due to Cooper Hospital expansion or because of rising housing costs. Through it all, “Pino has continued this work, redevelopment plan or no redevelopment plan,” says Olga. “He’s recruited other Lanning Square residents to do similar things on their blocks. And he now works part-time for a nonprofit housing developer, Camden Lutheran Housing, who hired him specifically to bring his program to the North Camden neighborhood.”

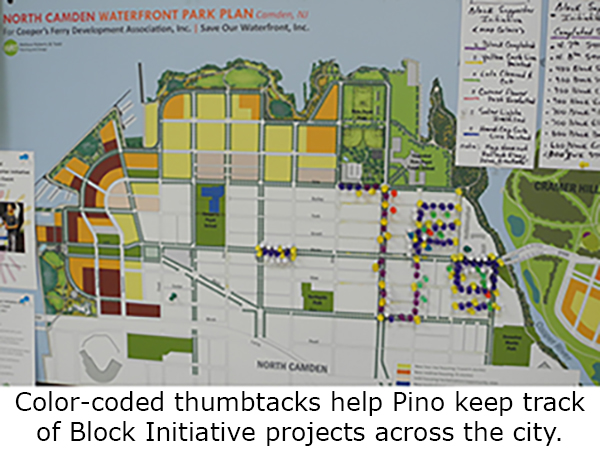

For Pino, it’s simple. People need hope. Since being hired by Camden Lutheran Housing to expand his program into North Camden, he organizes his activities in a large meeting room on Galindez Court. A map of North Camden is pinned to the wall, marked with colored thumbtacks to signify their progress in various neighborhoods. Most of the tacks are clustered around one section, expanding outward from where the program was introduced, save for two blocks outside of the cluster. After a shooting death in that area, Pino decided to deviate from his plan. He gathered up his tools and his candy cane decorations and he delivered hope to the people he felt needed it most.

Pino doesn’t knock on doors to introduce his Block Supporter Initiative. His approach is more subtle than that. He comes bearing gifts of flowers or decorations or whatever he’s been able to gather with his limited funds and gets right to work. When residents become curious and venture out to ask what he’s doing, he makes a straight-forward pitch. He will help organize efforts to beautify the neighborhood and, in return, they have to commit to cleaning up the street-facing side of their property, and keeping it that way. Many report having tried to make improvements in the past, only to give up out due to a lack of effort by both neighbors and city officials. But Pino’s contagious energy makes them want to try again. As they begin to take more pride in their home and their block, the excitement spreads and he fends off that communal depression with positivity—one small step at a time.

The Block Supporter Initiative has been so successful that Camden Lutheran Housing is taking the concept a step further. Through a new project leasing billboards, they hope to change the messaging in Camden—replacing ads such as Are you drowning in debt?, Do you need a divorce?, If you’ve got a heroin addiction…” with ones that say, A fresh start 2017, Be You!, Engage in School Activities, Welcome Home. Pino says people have called to say how much they like the change.

“You don’t need to see those kinds of negative billboards,” says Pino. “All it creates is negative things. You need to see positive things and move things in a positive way, and that’s one of the things that we’re also doing here in North Camden. And we hope also that the city will adopt things like that. … They need to create positive messages on those billboards and inspire instead of creating hopelessness.”

“We all deserve to have a better quality of life in front of our homes for our children.”

Ultimately, as Pino’s work expands throughout the city, his goal remains unchanged from the day he began this work nearly 15 years ago. “We all deserve to have a better quality of life in front of our homes for our children.” If that quality of life isn’t what it should be, due to poverty or crime or other social problems, the emphasis should be on addressing the problems, not removing the people. “All you have to do is fix the problems. Address those problems, and you can have better residents right here—right in the same city where these residents live.”

Back to Poverty in Focus

|